There is simply nothing more charming, intimate, and inviting than viewing great art in the setting of a private home or country house. It is one of the experiences our collectors and artists treasure most at each of our Collectors for Connoisseurship Arts Weekends that have been held in Atlanta, Denver, New York City, Savannah, and the Hamptons. This Fall, we plan to travel to the Hudson River Valley in upstate New York and will visit Kykuit, the remarkable Rockefeller country estate in Pocantico Hills.

In anticipation of future arts weekends, we recently traveled to North Carolina and visited the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem. The 1917 134-acre estate includes an historic home, man-made lake, golf course, formal gardens, forest, meadows, wetlands, and bucolic walking trails (open year-round) that are enjoyed by not only tourists but the local community.

The Reynolds estate, known as Reynolda was built by Richard Joshua Reynolds, founder of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (a pioneer in the advertising and manufacture of tobacco blends, including Camel cigarettes) and his wife Katherine Smith, an astute businesswoman who eventually purchased in her own name more than 1,000 acres as part of the estate. Katherine envisioned and supervised the building of a self-sufficient estate that included and boasted the most modern innovations in the running of the “model farm” described below.

Their daughter Mary and her husband Charles H Babcock, Sr. would eventually give 605 acres of the estate to Wake Forest University, including Reynolda Gardens and Reynolda Village. In 1964, Babcock founded a nonprofit (“Reynolda House, Inc.”) to provide public educational arts programming on the estate and in 2003, work was commenced on the Babcock Wing that now contains 31,619 square feet of museum space.

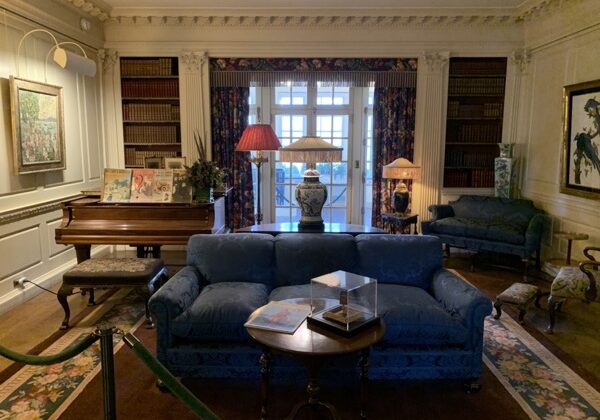

The centerpiece of the estate was the country house above which originally contained nine paintings of historic American art that became the origin of a broad sweeping collection of three hundred works from 1755 to present.

Before turning to the art collection, it is important to appreciate the historical architectural context of Reynolda. In the late 19th century, as American wealth was burgeoning and cities were experiencing explosive growth, successful urbanites in search of clean air and a more pleasant lifestyle started building “country houses” outside the cities to which they could commute for the weekend. The desire for “country living” by the wealthy produced an architectural “American Country House movement” that would flourish until the Great Depression.

Drawing upon the centuries-old British models where the country house was the center of social life for the elites, these country houses were built on large tracts of land which could be used for recreational pursuits such as riding and hunting. Although the American country house had its own unique style, the Gilded Age tycoons who had traveled on the continent sought to elevate their standing in the New World by referencing a variety of Old-World European styles found in England, France, Italy and Spain. These “houses” and “cottages” proclaimed wealth and status and were anything but intimate homes. Lavish and extensive country estates such as those built by the Vanderbilt family in Newport (“Marble House” and “The Breakers” Cottages) and Asheville (“The Biltmore”) announced that the Americans had arrived!

Notably, regardless of size or opulence, a central feature of these country houses were their gardens. “No feature of the American country house movement was as expressive of the desire for beauty in a rural setting as were its gardens and landscape architecture.” Traces, Spring 2003 at 36.

Indeed, to provide the residents and guests immediate access to the views and gardens, architectural features such as terraces, conservatories, gazebos and loggias became prevalent. Id. One of the greatest garden estates in this era was built by the Du Pont family in the Brandywine Valley which we visited several years ago on a Denver Art Museum tour. The stunning Longwood Gardens located on over one thousand acres with twenty outdoor gardens and a massive conservatory shown here are simply unrivaled.

Another typical feature of these country estates included farming complexes, known as “farm models” or “farm groups” that produced significant employment and became the hub of activity for local communities. For example, in 1901, the “Hyde Park Farms” shown here were built in NY by Frederick Vanderbilt who commissioned architect Alfred Hopkins and farm expert Edward Burnett to build a farm group that included many buildings needed for farming operations. Significantly, to carry on the bucolic and appealing sensibilities of the main house, much architectural attention was paid to these support buildings by architects such as Hopkins who added aesthetic design features that made them look like picturesque villages. Although these “gentleman farms” were not built to make money, the capitalists who built them were interested in the innovation of new agricultural methods and efficiencies as well as best practices in farm management. Hyde Park Farms, Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, National Park Service.

The Reynolda estate reflected this national country house movement with its country house and model farm. The gem of the elegant 34,000 square foot historic home is the collection of American art that spans 250 years from the 18th-20th centuries, including works by Frederic Edwin Church, John Singer Sargent, Martin Johnson Heade, William Michael Harnett, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Jacob Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alexander Calder, Lee Krasner, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol.

The genesis of the collection included works from the Hudson River school which romanticized the vast, unexplored landscape of the American continent and elevated the genre of landscape to religious expression. The school is well represented with works by Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, Jasper Francis Cropsey and more.

From the Hudson River Valley in NY to the West and beyond, these artists painted large-scale landscapes that subtly invited viewers to consider often competing religious and scientific philosophies such as “manifest destiny” and Darwinism. As explained by the Reynolda, the stunning and sublime luminist painting by Frederic Church shown here (“The Andes of Ecuador”) attempts to reconcile such tension. The apparent reference to the divine presence in nature demonstrated by the predominance of sky and light along with the small praying figures makes a religious statement while incorporating intricately detailed botanical and biological elements associated with Darwin. See Reynolda Department of American Art Description.

Befitting such an elegant mansion, portraits by Gilbert Stuart and John Singer Sargent, two of America’s foremost 18-19th century portrait painters grace the walls of several of the main floor rooms which are also filled with many decorative arts objects that comprise the extensive collection of 6,000 historic objects.

Continuing the journey to the upstairs reached by the fabulous grand staircase shown above, we encounter the diverse modern and contemporary art at Reynolda. A veritable who’s who collection of works of 20th-21st century American artists resides there in room after room. On view include Grant Wood, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis, Milton Avery, Alexander Calder, Alice Neel, and Lee Krasner. Not on view although the collection is rotated frequently are works by Arthur Dove, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Chuck Close, Jim Dine, Sam Francis, and Philip Pearlstein.

Striking and close to home is the recent work in 2022 by Stephen Towns entitled “Flora and Lillie” which is a painting of two of the residents of Five Row, the segregated village built for employees and families living on Reynolda from 1916 to 1960. Based on a photograph and his research during a residency about Black labor in the South, Towns pays tribute to the workers who were so critical to the success of the model farm and estate at Reynolda and throughout the region. Surrounded by Southern flora, an intentional reference by the artist to “Flora,” the captivating and charming figures convey the beauty, strength, and grace of those who labored there.

Be sure to visit the display in the museum building connected to the historic house that explores the interesting history of the innovations and practices at Reynolda. And do make time to stroll the lovely park-like grounds and gardens.

For further information about the American Country House movement and the efforts to preserve important country houses, visit the American Country House Foundation.

Shannon Robinson is the curator and chairperson of the biennial exhibition Windows to the Divine and the annual symposia by Collectors for Connoisseurship (C4C). Past C4C events