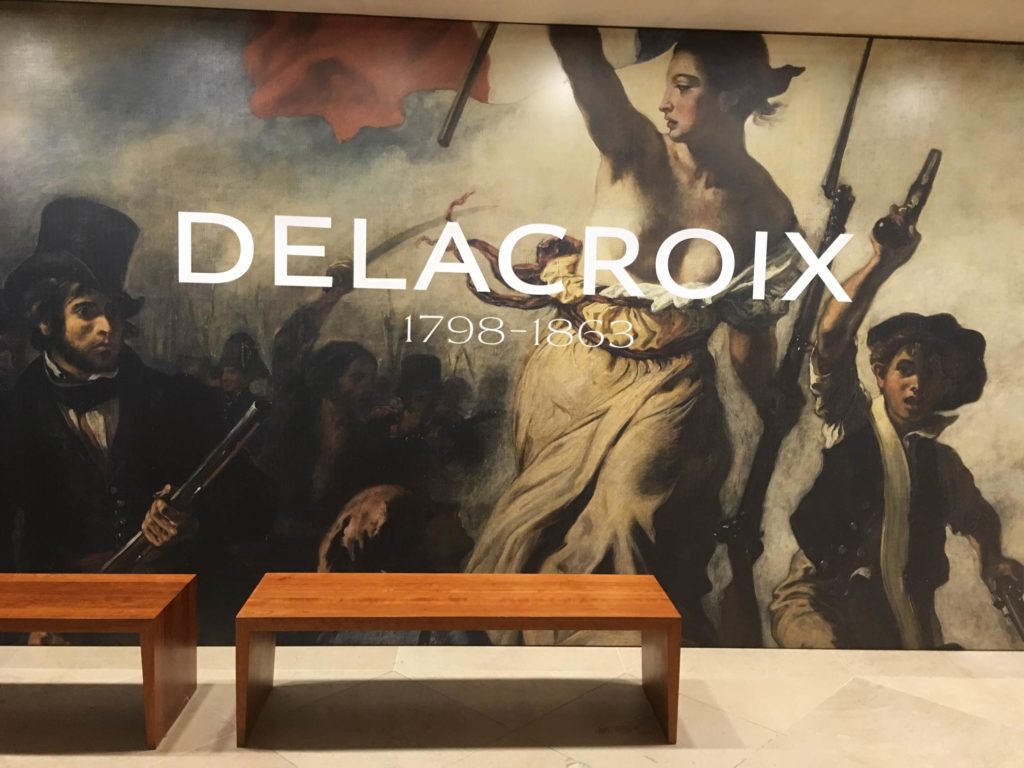

During our recent C4C trip to Paris, we were able to view the historic retrospective exhibition being held from March 29th to July 23rd at the Louvre Museum featuring 180 works by one of the titans of French painting—Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). The last major retrospective was held in Paris in 1963 on the 100th anniversary of the painter’s death.

While Delacroix is universally celebrated as the leading proponent of the “Romanticism” movement of the 1800’s this exhibition does not focus on the age-old debates about the competing 19th century “isms” and how his work did or did not qualify as “romantic,” but rather, invites the viewer to learn more about the artists’ character, his multi-faceted interests and the inspirations behind his successful 40-year career.

Two of the most striking observations about his character and interests are that he was extremely ambitious, entrepreneurial and successful at a young age and was a dedicated writer as well as painter. Writing was a regular activity for him as he wrote brilliant letters to friends, penned articles attacking art critics and wrote the “Journal” that was an important account of himself and his life. The writings of others were also strong influences on him and his work, including Byron, Goethe and Shakespeare (with the latter two being the sources of many lithographs produced by Delacroix in the late 1820’s). Indeed, rather than surrounding himself with his fellow artists, Delacroix’ passion for literature as well as music lead him to develop relationships with writers such as Alexandre Dumas and George Sand and the composer Frederic Chopin. And while he preferred the company of such friends, Delacroix also appreciated the importance of cultivating relationships that would further his career which is why he frequented salons and was even a member of the Paris City Council.

As the youngest child of a bourgeois family of the Napoleonic empire (his father was an ambassador and prefect and his brother, a general and baron) that was financially ruined and left him an orphan at the age of 17, Delacroix had a driving need for fame and glory which he sought to achieve through his painting. In his youth, at the age of 26, he achieved acclaim for his masterful contemporary history painting, The Massacre at Chios (1821 Greek revolt against Ottoman Empire occupation), which Delacroix painted in 1824 and exhibited in the Salon that year (building on the earlier success of The Barque of Dante exhibited in the Salon of 1822). And nearly two centuries later, when the 21st century viewer stands in front of this monumental (4 meters in height) breathtaking depiction of the massacre of twenty thousand men, women and children, it is no wonder that the work received so much attention and praise by writers of the day such as Baudelaire who was so moved by its powerful portrayal of the barbarism of man.

Having established himself as a prominent and successful French painter, Delacroix turned his attention away from history paintings. Inspired by the landscapes of John Constable and portraits by Thomas Lawrence, in 1825, he traveled to England and thereafter began experimenting with compositions that combined the lesser painting genres such as portraits or still life with a landscape as well as animal scenes that were given the gravitas of a portrait such as Young Tiger Playing with its Mother.

In 1827, having achieved so much success, and inspired by Lord Byron’s poem of 1821 about the slaying of all of the possessions (wives, pages, horses and dogs) of the Assyrian King Sardanapalus prior to his own suicide, Delacroix abandoned any need to embrace classical and moral conventions and focused on the surface (gleaming skin and shimmering fabrics) of the canvas rather than its structure and anatomical accuracy by painting The Death of Sardanapalus. While the drama, emotion and opulence of the painting firmly established Delacroix as a “romantic” painter, the writhing orgiastic figures were considered scandalous and were subsequently rejected by the Salon.

After his successful iconic painting of the more acceptable Liberty Leading the People (shown above on opening wall of exhibition and hung in the Salon of 1831) which depicted the 1830 revolt by the people of Paris, Delacroix sought new inspiration during his 1832 travels to Morocco. There, he became enthralled with the colorful and exotic scenes of contemporary Moroccan society that were more akin to reenactments of classical history than the urban scenes that were now becoming the subject of the realist movement in France. Unlike The Death of Sardanapalus, as noted in this exhibition, with works such as the Women of Algiers in their Apartment, which he exhibited at the Salon of 1834, Delacroix was “able to explore the decorative force of his painting without depending on drama and passion.”

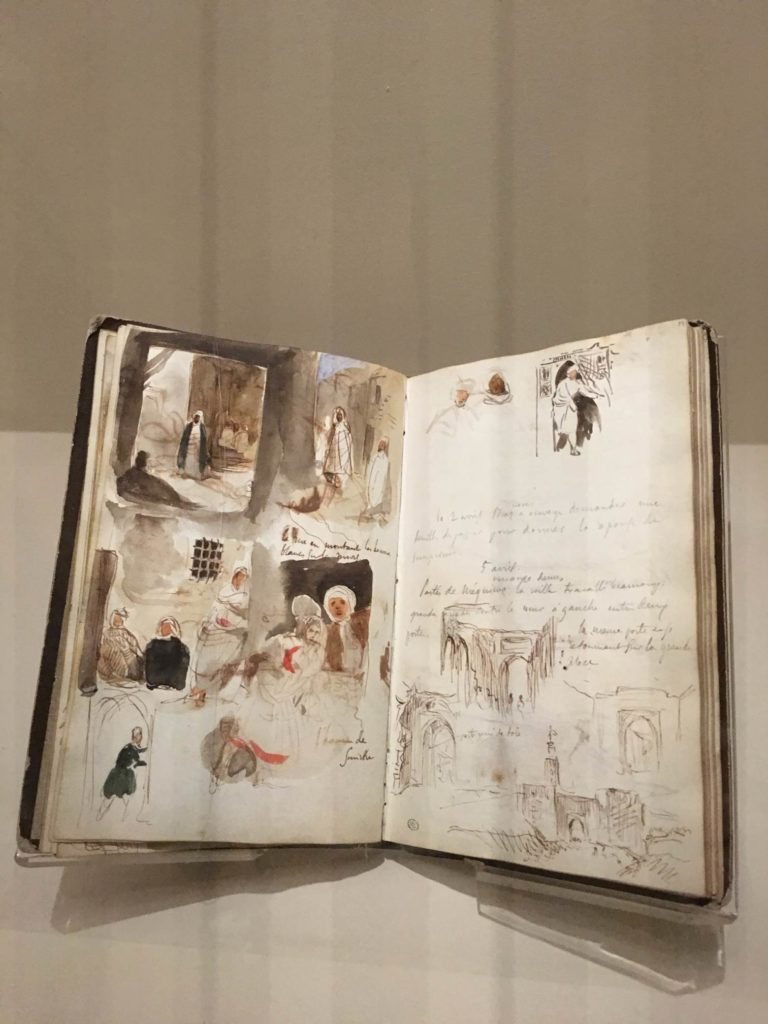

Indeed, seeing so many of these Moroccan inspired decorative works in one exhibition was noteworthy. It was also interesting to examine his albums of drawings and notes which inspired Delacroix to paint over 72 paintings based on Morocco over the remainder of his life.

In conclusion, the exhibit curators summarized: “Delacroix’s oeuvre, which retained its coherence despite its successive changes, seems best defined by a quest for singularity and a belief in the expressive power of painting, rather than by the elusive term ‘Romanticism’.”

Shannon Robinson is the curator and chairperson of the biannual exhibition Windows to the Divine and the annual events by Collectors for Connoisseurship (most recently April 12-14, 2018 in Denver and May 23-26 in Paris).